The case for/against replicas

The ethical issues surrounding replica fashion are well documented and yet, they are more popular than ever. Why?

Campaign image from Gucci’s Fake Not collection from Fall/Winter 2020-21 by Alessandro Michele.

As someone who grew up in a small North East Indian town with easy access — capital withstanding — to Bangkok and tons of fashion replicas at my literal doorstep, I think I know a thing or two about dupes. This is why the discourse surrounding wearing fakes, with its over-intellectualisation, virtue signalling, and general snobbery, is fascinating to me. Growing up, I assumed wearing certain brands or coveted items was a true marker of wealth and taste. Then, during my teenage I made a trip to New Delhi — arguably the only metropolis in India that has harsh winters making layering possible; layering equals a focus on clothes and proportions versus one's physical likeness — for the first time and through direct exposure understood that you can hoard accumulate wealth but you cannot buy taste.

Around the same trip, the fact that almost everything fashion-related being sold in my hometown was fake started registering in my head. I was naive and genuinely thought you could get away with buying a 'Chanel' bag for less than 5000 INR or approximately 59 USD. I had seen plenty of 'Chanel' bags in real life, but I had not set foot in or even seen a single physical Chanel boutique in my life up until that point. It should've been my clue, but I digress. Circling back to my experience in New Delhi —and btw this is not a slight on New Delhi fashion because, let's be honest, rich people not having taste is not just a New Delhi thing but rather a universal thing — I wondered as to why the much more affluent women of the capital, trotting their latest handbags on their arms did not look quite as fashionable as their small-town counterparts who I grew up watching every day.

It was not unusual to have shops in my hometown — stuffed to the brim with fake goods — mimic the ones in Bangkok, as pictured above. Source.

I have ruminated about this for years, and like every other fashion-related conversation, it comes down to taste and intention. For example, when you buy a Chanel bag, real or otherwise, the motive behind the purchase matters. Was it a decision influenced by a personal interest in a specific collection or a specific Chanel muse, or was it driven purely by the intention to project great wealth? I was not as enamoured by the style of New Delhi women then because it wanted to communicate wealth to me as a spectator, and perhaps the opposite was true for their small-town counterparts. Scarcity does indeed breed creativity, after all.

Does exhibitionism of excellent taste through replicas suddenly erase their unethical and borderline illegal backgrounds?

The obvious answer is no. But, discourse cannot be had about this topic without acknowledging the many nuances in this conversation that are often untouched. Advocates of authentic fashion items will argue that purchasing a replica item directly supports illegal activity and copyright theft (copyright law is also a highly contentious and ambiguous territory). However, they will not entertain the possibility that consumers already know this and address why they do not care.

Years ago, I remember watching the Birkin-centred Sex and the City episode from 2001, where Lucy Liu makes a quick cameo. A Hermes sales assistant quotes the price of a Birkin at 4000 USD to Samantha and casually mentions a three-year-long waitlist. Exclusivity has always been a Hermes thing, but the quoted price of the bag, even after considering inflation, is much lower than what the brand currently charges for the bag. The ridiculousness of the quota system is a whole separate conversation.

One might assume that only brands like Hermes or Chanel are guilty of pricing their items to an exorbitant level to spike demand and scarcity. However, even newer brands are just as guilty of this phenomenon, though one might not fault them as much. Especially given how difficult it is to financially sustain an up-and-coming fashion business. A slight digression here, but regardless of the challenging circumstances, I cannot believe Khaite, a brand not even a decade old, is charging upwards of 2500 USD for some of its Alaïa replica adjacent bags. Daylight robbery? I think so.

Pricing issues across different brands might be prominent drivers of an upsurge in the popularity of replica fashion. Primarily because brands have lost interest in fostering relationships with first-time buyers. Consumers at higher echelons will have no trouble shelling out money regardless of how often a brand might hike their prices yearly. The luxury business, however, is just as much about seasoned shoppers as it is about first-time shoppers intending to use luxury goods as a marker of their upward class movement. Especially in developing nations that are transforming into global power players.

The pendulum of quality.

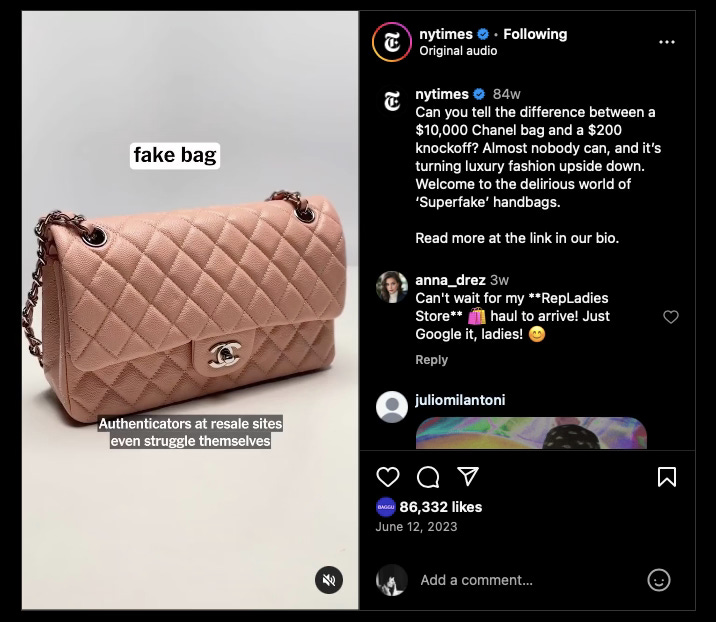

TikTok is light years away from being a reliable source of accurate information. Still, the amount of content on the appdocumenting the degrading quality of luxury goods today, especially the Chanels, is just un-ignorable. The loud chatter over the depleting quality of luxury goods on TikTok is surprisingly also in alignment with the whispers on Reddit. The discourse is not as heightened as on TikTok, yet it can escalate similarly fast in virality and toxicity. The consensus around the depletion of the quality of authentic fashion items is nearly unanimous across users from both apps/websites.

Do you know what else they are in complete agreement about? The excellent and un-clockable quality of some of the super fakes. Before delving deeper into the replica or rep culture of handbag Reddit, I assumed that AliExpress & DHgate were the places to go for super fakes. Consider my surprise when I learned that people on the same Reddit avoid purchasing replicas from these listed websites and actively look down upon them. Instead, these shoppers purchase and negotiate different features of replica goods through direct private channels to China-based sellers on WhatsApp and WeChat. It is not enough for a replica to just look the part. Not anymore.

Empty promises.

Another reason why consumers gravitate towards rep culture regardless of its apparent pitfalls is because of the many unspoken, empty promises that are expected from luxury houses, in general. When you buy a luxury item, apart from being a marker of wealth, it is also meant to signify the brand's rich history, the outstanding artistry of its artisans, and the innovation of its creative director. Do brands today even try to fulfil these promises? I don't think so. Maybe it is the consumer's fault to expect so much of brands when they do not even explicitly make these promises, but you and I both know that that is bullshit.

For the 1%, it may not matter when Chanel stopped using 24k gold-plated hardware in 2008, as it continued to hike its handbag prices. But for the rest of us, those unspoken promises of history, artistry, innovation, and quality make us want to tap into the fantasy and rationalise such an enormous purchase.

There is a video story from NYT on fake bags that influenced this story. It is on Instagram and TikTok but for whatever reason I am not able to do the usual copy paste. Substack will not allow it, so here’s the link. The written accompaniment is just as interesting and well-written but is far too directional in how to purchase these super fakes lol! Read it here.

The fantasy is waning.

I remember when Dries Van Noten announced his retirement, and out of respect, I watched a fashion documentary about him. In it, he mentions the early aughts when collections became increasingly about handbags as they became a brand's most profitable output. I do not remember him saying anything about the luxury conglomerates. Still, I wondered about what opinions he must hold about them — as someone whose brand remained independent for much of his design career — and the absolute dearth of creativity they have brought upon the industry with their fixation on profits and their inability to nurture their creative directors for an extended period.

The fantasy is waning because of how much stuff is getting churned out collection after collection by burned-out designers. Consumers also sense it, and the more the gatekeepers of luxury use ethics or quality as a crutch to berate people for their choices, the higher the rep industry will boom. Also, how hypocritical to pretend that the luxury fashion industry is operating on a squeaky, clean slate. There are controversies galore, with the faux pas from Dior and Loro Piana being the freshest ones in my mind.

So, ultimately, what should you do? Should you buy that cheap rep online, or should you wait, save money, and make that authentic purchase a few years later? I would have leaned towards the latter a few years ago, but now, increasingly, I find myself rationalising the former.